The OTHER problem with pay-to-play

Inequity is only the tip of the iceberg

The standard critique of Canada and America’s pay-to-play model of youth soccer development—in which parents are responsible for paying for registration fees, travel and tournament costs, uniforms, etc.—is that it is fundamentally inequitable.

This is, of course, true. While preternaturally talented U12s will receive formal (or informal) financial assistance from an interested youth soccer club, kids who are less obvious standouts but who have real potential to succeed will get left behind for the crime of not having wealthier parents.

This is particularly devastating in places like Canada, where scouts tend to focus primarily on the top youth development leagues, such as OPDL in Ontario.

Moreover, this lack of equity also extends between provinces.

The Nova Scotia Soccer League registration costs, for example, are roughly one-tenth of those in Ontario, an astonishing accessibility gap that is only partially closed by the fact that Ontario arguably has better coaching and playing resources.

Alright, you might be thinking, that sucks for the poor kids who aren’t Lamine Yamal, but at least the kids in the league will get their shot.

Unfortunately, as we’ll see, pay-to-play also hinders youth development for the kids who can afford it, and not only because they are being denied the chance to play in a deeper talent pool (I strongly suspect this dynamic is also at play for the girls’ teams as well).

Great youth teams don’t always produce great senior players

This past weekend, I watched my son’s club—currently in the middle-lower end of the league table—play the best team in his OPDL age group. I was excited to see Ontario’s best youth soccer club.

What I witnessed on the pitch, however, will be familiar to many parents of pay-to-play development leagues.

The team was roughly half a foot taller than the boys in our team. The back line was a good foot taller or more. Their wingers were extremely fast, though not necessarily otherworldly in possession.

Tactically, their approach could not have been more obvious. The well-organized, freakishly tall backline would patiently pass the ball, wait for one of their speedy wingers to initiate a diagonal run, and then ping it downfield in the hopes they might latch onto it, something that happened maybe once out of every four attempts. All of the club’s players had been drilled repeatedly to take only a few touches.

Graham Taylor would have been proud.

Though our club’s high block and discipline in avoiding a high press were effective for most of the game, our luck ran out late in the final stages, and we let a few soft goals in.

The team we faced is one of roughly three or four clubs in the league that dominate OPDL every year. On the evidence so far, each of these teams, with some important exceptions, plays more or less a similar style (Vaughan so far has bucked the trend).

These clubs’ players also fill out most of the youth provincial teams. They enjoy some of the top coaching talents in the country. And they produce professional players and the odd national team regular.

But most of their pro soccer grads aren’t likely players you’ve heard of. Quite a few are in the Canadian Premier League. Many received D1 scholarships to play in the NCAA.

So what? You might be thinking. There’s nothing wrong with journeymen footballers, and the more Ontario produces, the more likely a few are to reach Alphonso Davies-type greatness. Ontario is never going to have the same number of scouting eyeballs as a European academy side or MLS Next team.

These are fair points, but the fact of the matter is that while Ontario enjoys some truly perennially dominant youth clubs, it lacks a single, standout producer of consistently international-calibre talent.

Parents don’t pay to develop their kids, they pay to win

There may be one exception to this in Ontario, however: Brampton Youth SC. The club, now no longer in OPDL, has trained players including Tajon Buchanan, Jonathon Osorio and Cyle Larin, Jayden Nelson and others, and makes up an outsized portion of Canada’s men’s national team players.

Interestingly, despite Brampton’s historic pedigree, the club never lit up the OPDL league standings. I don’t know exactly why, but knowing a few things about Ontario soccer now, I would venture to guess it might be because the club has historically favoured technical ability over size and speed.

While this preference is great for developing professional footballers, it’s not great for winning youth soccer matches. No matter how technically skilled your players are, unless you’re La Masia, it’s going to be difficult for your kids to compete against teams stacked with near 6-foot fourteen-year-old defenders and wingers who are track stars but might not be able to dribble for more than a few yards at a time.

This is how it should be, of course. Youth soccer is awash in reminders that the results don’t matter as much as the training, the experience, the learning, the growth, the technical ability.

The problem is that pay-to-play strongly disincentivizes this ethos. Because while parents know, at least intellectually, that winning isn’t everything, they also reasonably believe that their kid is less likely to earn attention from pro clubs or D1 American universities if they’re stuck on a losing team. Certainly, Ontario’s annual selection of provincial call-ups would back that up, dominated as it is by the OPDL’s winningest clubs.

And the clubs know that, despite OPDL’s ostensible insistence that kids play for their nearest local team, losing makes it more difficult to recruit players and their families, not just for OPDL, but for lucrative house and rep leagues.

So, size and speed win out over technique in tryouts. Coaches, feeling pressure to win at all costs to keep up demand for registration spots, will succumb to the temptation to play long ball rather than work the ball from back to front, even at the sacrifice of training smarter, more resilient footballers. Kids who might be extremely adept on the ball but who aren’t elite sprinters or enjoying an early growth spurt will lose their spot.

Of course, size and speed are important pro footballing qualities. The problem, however, is that as players age, these attributes matter less. Despite years of elite-level coaching, these players will struggle to compete against international peers who have the same height and speed but are simply far more confident on the ball and intelligent off it.

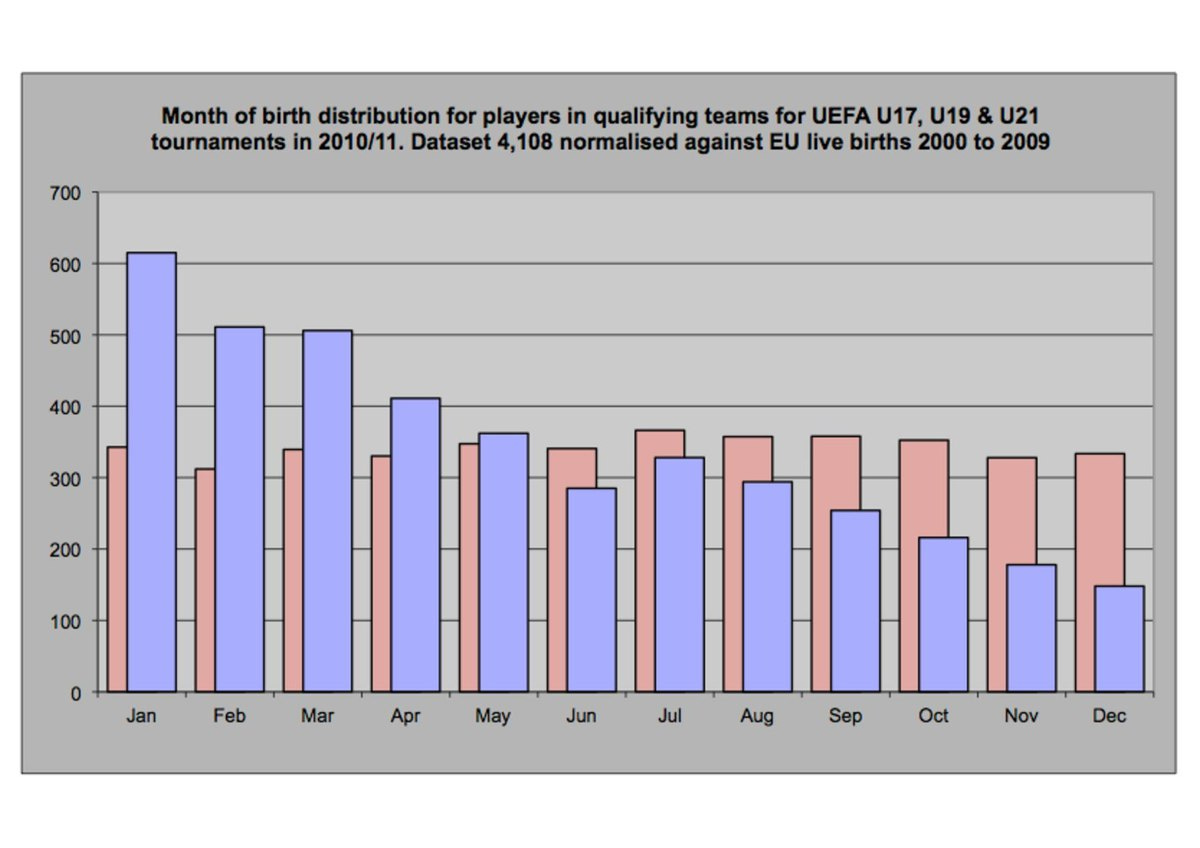

This is part of the relative age effect, in which youth teams select kids born earlier in the year because they are more developed (ie bigger and faster). The chart below gives you an idea of how it works in practice.

I’ve yet to see how Ontario soccer has meaningfully tried to address this issue, but I have definitely seen how it affects how teams play on the pitch.

Solving the perverse incentives of pay-to-play isn’t easy. It will require Ontario to find ways to counter the relative age effect, and government investment to reduce the need for clubs to sacrifice long-term player development for trophies. But there is a reason why so many of Canada’s best players left the country at a young age to play in Europe or America.

And it doesn’t have to be this way.

Hi all, today’s post at Sing Palestine Vivra is a tribute to the soccer fans (and player) around the world, who have publicly displayed support for the Palestinian people. The fans are stepping up, but where are the players? And we need to hear from other sports -cricket, field hockey, tennis, volleyball, table tennis, basketball, baseball, rugby, golf, American football and ice hockey.

https://open.substack.com/pub/jeffhoulahan/p/sounds-for-palestine-day-13?r=604ds6&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=true

We’ve started Sing Palestine Vivra to encourage people to make public demonstrations of support for the people of Palestine. Eventually, we hope to be able to use Sing Palestine Vivra to organize large scale campaigns of public demonstrations of support for Palestinians.

The substack Sing Palestine Vivra will never accept donations or paid subscriptions.

In Solidarity and with Hand to Heart, Palestine Vivra